Post: Cert Transparency #1 - PKI and Cert Transparency

Overview

If you are operating a server, you may have encountered issues related to Certificate Transparency. This post is written for those who are not familiar with electronic signatures, PKI, and Certificate Transparency, summarizing what I know about these topics.

First, let’s discuss encryption and PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) for those who might not be familiar with them. If you already understand, you can skip ahead to Certificate Transparency.

Electronic Signature

To understand PKI, it’s essential to grasp the concept of electronic signatures, which requires an understanding of the emergence of PKI. Scholars have long pondered asymmetric key encryption algorithms. As the name suggests, prior to its introduction, only symmetric key encryption was possible. In symmetric key encryption, as inferred from its name, both the sender and receiver use the same key for encryption and decryption. How about in asymmetric key? The keys used for encryption and decryption by the sender and receiver are different. Encryption algorithms primarily aimed to prevent eavesdropping during communication.

There were two problems that couldn’t be resolved with symmetric key encryption algorithms alone during communication:

- The receiver needs the key to decrypt, but how can one ensure it won’t be intercepted while being transmitted?

- How can the receiver be sure that the sender is indeed who they claim to be, instead of an imposter?

This is why asymmetric keys were so desirable. If you encrypt with key A, you need corresponding key B for decryption, and vice versa. This provides a fantastic solution:

- Premise: Each participant in communication has an asymmetric key pair, one private key (not disclosed to anyone) and one public key (disclosed to everyone).

- The receiver gives their public key to the sender, who then encrypts the plaintext with it. Thus, only the receiver can decrypt it.1

- The sender encrypts the content with their private key. The receiver, knowing the sender’s public key, can decrypt it. If the decrypted value matches the sent data, the sender is confirmed to possess the key pair.

Thus, it’s a remarkable solution to the previously mentioned problems! The second concept here is electronic signature. It allows proving in communication that the other party owns the private key and that the data sent by them indeed comes from the person who owns that key.

PKI

Though the diagram might look a bit outdated, let’s appreciate the person who drew it.

As differentiating communication counterparts became possible through electronic signatures, there arose a need to authenticate entities in the physical world. For example, how can a shopping site trust that a person claiming to use a debit card for payment is actually that person? Or how can I be sure that the website I’m accessing in my browser isn’t a phishing site?

In the real world, a trustworthy entity can certify another by verifying their identity and key pair, storing the public key. Anyone on the internet can then access this public key and the associated identity information. The bundle of information, including the public key and identity, is called a certificate. It’s the familiar public key certificate, also represented by the lock icon you see when accessing websites.

In the depicted diagram, there are several players involved. The person with the key is the subject, the owner of the certificate. CA (Certificate Authority) verifies the subject’s identity and manages certificate issuance or revocation. RA (Registration Authority) assists in verifying the subject’s identity and issuing certificates on behalf of a CA (banks can serve as RA in scenarios for acquiring public certificates). VA (Validation Authority) validates the certificate’s authenticity. From a practical standpoint, CA and VA’s roles are often merged into one entity.

The diagram illustrates the process of a subject obtaining a certificate, using it to authenticate themselves to an online shopping site, and the site verifying the certificate’s validity.

To ensure the certificate truly belongs to the mentioned person, two verifications are needed:

- Whether the certificate has been revoked2 or is fraudulent.

- Whether it’s issued by a CA that you trust.

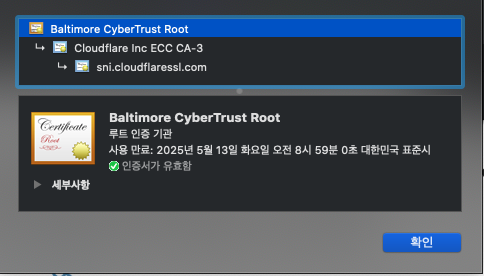

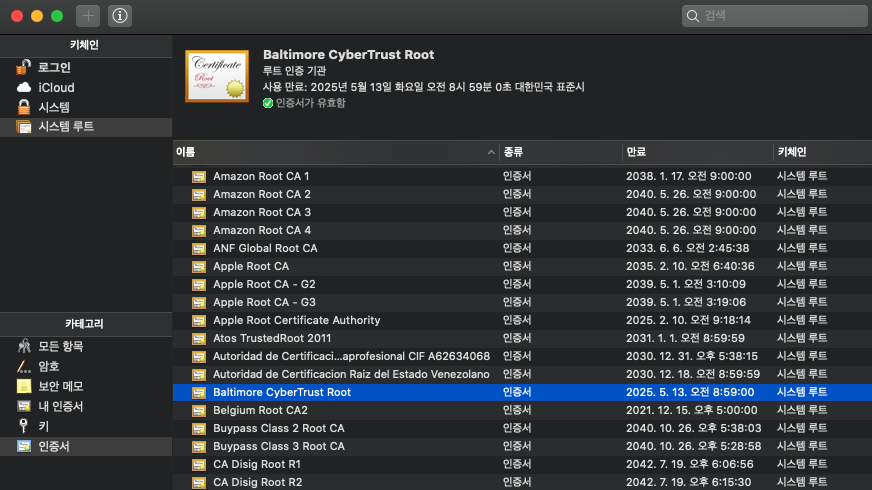

Revocations are managed via CRL (Certificate Revocation List) issued by CAs. It lists certificates that have been revoked or altered. The second verification involves what’s known as a certificate chain, where a certificate is signed by its CA using the CA’s private key. This chain of trust can be traced back to a root certificate, which is self-signed and issued by a trusted authority.

Interestingly, even if a certificate throws an error for being bad, the security of SSL/TLS communication isn’t compromised since the key pair in the certificate still functions correctly. However, it can’t guarantee that you’re communicating with a trustworthy individual.

Systems using certificates store a collection of trusted CAs. For example, your computer might have these stored.

If you’re using Chrome, you can view the trusted CA certificates by navigating to Settings -> Privacy and Security -> Security -> Manage Certificates.

While earlier examples involved shopping sites authenticating individuals, the use of personal certificates for such authentication has largely diminished3. Nowadays, most sites use certificates to ensure user safety.

For example, when accessing google.com, how can you be sure it’s really Google and not a phishing site redirected by a hacked domain server?

By accessing google.com via HTTPS, the server’s certificate helps confirm that it’s truly Google based on a certificate issued by a CA I trust.

Certificate Transparency

Finally, let’s talk about Certificate Transparency. What issues required its introduction?

Reading the above, you might sense some discomfort. What if someone fraudulently obtains a certificate for my domain? Or what if a CA mistakenly or unwittingly issues a certificate to an impostor? If CAs solely manage their certificates, what happens when mistakes occur?

This led to the development of Certificate Transparency, which differs from traditional PKI in several ways:

- When issuing a new certificate, CAs must log the issuance in an append-only (immutable) ledger.

- Domain owners can subscribe to monitors to be alerted about new certificates issued for their domain.

- Monitors keep an eye on logs and notify domain owners when a new certificate for their subscribed domain is issued.

- User agents (HTTP Clients, primarily browsers) reject certificates that don’t ensure Certificate Transparency.

In essence, Certificate Transparency serves as an extended system enabling transparent certificate issuance, unresolved by traditional PKI frameworks. The Certificate Transparency project, initiated by Google, began implementing this policy in Chrome since 2018.

While traditional certificate users (owners or end-users) aren’t significantly affected, the system requires active participation from certification authorities.

This post focused on the basics of PKI and electronic signatures due to space constraints. Specifics on the Certificate Transparency framework will be discussed in a later post.

-

Assuming the asymmetric encryption algorithm remains unbroken… ↩

-

Certificates can be revoked or suspended at the owner’s request, such as if the private key and its password are compromised, to prevent misuse. ↩

-

But you’re likely using them indirectly. Scenarios where individuals manually manage their private keys have almost disappeared worldwide. ↩